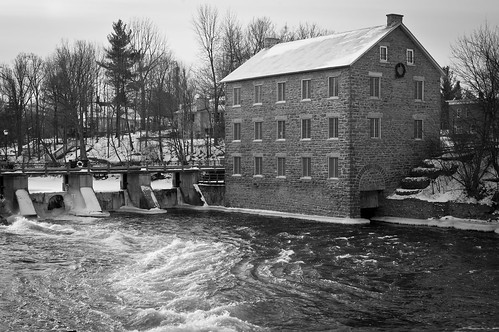

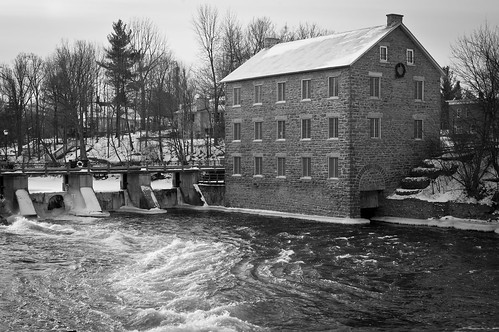

I may have mentioned that I am newly infatuated with Watson’s Mill, the historical centerpiece of Manotick and barely a few steps’ walk from the new house.

Since we moved in, I’ve been itching to get out there with my camera and simply wander around for a bit. It was Christmas morning, in fact, after everyone had settled in after breakfast to play with their toys and I needed some fresh air, that I finally managed to creep out with my Nikon.

I wandered over the dam and around the grounds, and these frost-patterned windows with their Christmas wreaths caught my eye.

It was only later in the weekend that the hair on the back of my neck stood on end when I thought about taking these pictures. I was reading up on the history of Manotick (a post for another day) when I came across references to the haunting of Watson’s Mill. I’d heard about the Mill’s ghost before, and in fact there was even a Haunted Ottawa presentation at the Mill just a couple of days after we moved in, but somehow I’d completely forgotten about it when I was creeping around with my camera in the gloaming.

The more I read, the more fascinated — and unnerved — I became. Do you know the story of Ottawa’s most haunted place?

The Mill was built in 1860 by partners Moss Dickenson and Joseph Currier. It’s one of the few remaining operational grist mills (it uses the current of the Rideau River to grind wheat into flour) in North America. Shortly after it was built, Joseph Currier met his second bride-to-be, Anne Crosby, in Lake George, New York. She had never been to Manotick, and after their January 1861 wedding and month-long honeymoon, he brought her home to celebrate the Mill’s first year of operation. It was March 11, 1861 — almost 150 years to this very day.

By all accounts, Anne was delighted with her new husband and new home. On her first day in Manotick, Currier brought his new bride to show off the Mill. As she was ascending the stairs to the second floor, her long, hooped crinoline got caught in a piece of machinery, and she was flung against a support post and killed instantly.

Currier never set foot in the Mill nor Manotick again. He went on to become a Member of Parliament, and eight years later married his third wife, the granddaughter of Philemon Wright. He commissioned a house be built for her as a wedding gift, and called it Gorffwysfa, Welsh for “place of rest.” The address? 24 Sussex Drive.

As for poor Anne, she never left the Mill. Visitors to the Mill report chills and goosebumps when they mount the stairs to the second floor on even the hottest summer days.

When I read this account, from an undated Ottawa Citizen story, the hair stood up not just on my neck but all the way down my arms, too.

But in 1980, two boys were walking across the dam beside the mill, the old lamps along the pathway giving off a pale, yellow glow in the deepening twilight. As they approached the mill, they heard a noise from above, like someone falling. They looked up to see a woman in a long skirt, standing at the window watching them. They froze. The ghostly figure tilted her head, and the boys grabbed each other and ran. Keeping their eyes on the window, they saw Ann slip away, and then reappear in the next window, following them.

Over the years, Ann has been seen more often. She’s become possessive of her mill, and doesn’t like things changed. If tour guides move anything, they’ll come in the next day to find it moved back to where Ann wants it.

Her footsteps, pacing along the second floor, are getting louder. Some people say it’s because she knows her secret is out, so she doesn’t have to hide in the darkness anymore.

But in the cold winter months, when the mill is closed to visitors, Ann gets lonely. She comes out, sometimes walking along the front of the mill, but mainly watching people from her favorite window by the pathway.

If you walk by, late on a winter night, you can sometimes hear her low, mournful voice, calling to the people below.

Since I read this account, I’ve been back to the Mill a couple of times. I won’t stop wandering around, and I won’t stop pointing my lens at it. In fact, it’s on the route of my favourite Manotick walk.

But I find myself cringing, trying very hard not to hear anything out of the ordinary as I cross the dam and mount the steps beside the Mill, willfully concentrating on the snow-covered steps and not the old Mill with its second-floor windows looming over me.

And when I do take my pictures, I won’t look too carefully through the viewfinder, either, lest I catch a glimpse of poor Anne Crosby Currier, lost 150 years ago.